Newton meets AI

View Sequence overviewStudents will:

- examine a number of variations of the Trolley problem and how it could relate to autonomous cars.

- compare consequentialist and deontological approaches to ethics.

Students will represent their understanding as they:

- identify the possible actions an autonomous car could take.

- compare the actions of an autonomous car selected as a result of a consequentialist approach and a deontological approach.

In this lesson, assessment is formative.

Feedback might focus on:

- students’ ability to describe the values and needs of society and how they influence the focus of scientific research.

- students’ ability to construct logical arguments based on analysis of a variety of evidence to support conclusions and evaluate claims.

Whole class

Newton meets AI Resource PowerPoint

Video: The ethical dilemma of self-driving cars - Patrick Lin (4:15)

Each group

Ethical dilemmas Resource cards (laminated for future use)

Each student

Individual science notebook

Ethical dilemma Resource sheet

Lesson

Re-orient

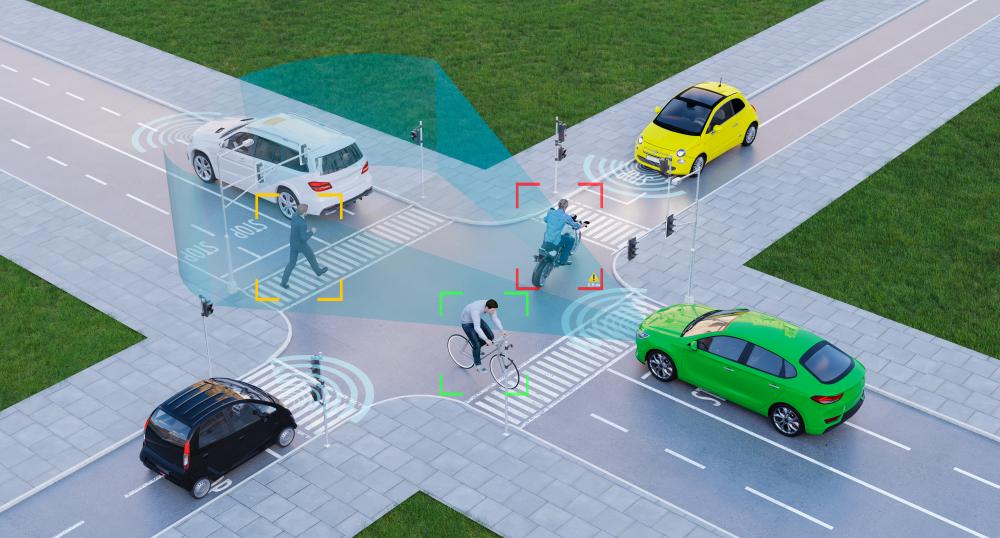

Review how quickly autonomous cars react and the factors that need to be considered when planning for autonomous driving.

These may include:

- the speed the car is travelling.

- the conditions of the tyres, road, and weather.

- the number of people in the car (mass).

- the use of seatbelts.

The Inquire phase allows students to cycle progressively and with increasing complexity through the key science ideas related to the core concepts. Each Inquire cycle is divided into three teaching and learning routines that allow students to systematically build their knowledge and skills in science and incorporate this into their current understanding of the world.

When designing a teaching sequence, it is important to consider the knowledge and skills that students will need in the final Act phase. Consider what the students already know and identify the steps that need to be taken to reach the level required. How could you facilitate students’ understanding at each step? What investigations could be designed to build the skills at each step?

Read more about using the LIA FrameworkIdentifying and constructing questions is the creative driver of the inquiry process. It allows students to explore what they know and how they know it. During the Inquire phase of the LIA Framework, the Question routine allows for past activities to be reviewed and to set the scene for the investigation that students will undertake. The use of effective questioning techniques can influence students’ view and interpretation of upcoming content, open them to exploration and link to their current interests and science capital.

When designing a teaching sequence, it is important to spend some time considering the mindset of students at the start of each Inquire phase. What do you want students to be thinking about, what do they already know and what is the best way for them to approach the task? What might tap into their curiosity?

Read more about using the LIA FrameworkSelf-driving cars

(Slide 77) Pose the question: What should autonomous cars be programmed to do in an accident?

Show The ethical dilemma of self-driving cars - Patrick Lin (4:15).

The Inquire phase allows students to cycle progressively and with increasing complexity through the key science ideas related to the core concepts. Each Inquire cycle is divided into three teaching and learning routines that allow students to systematically build their knowledge and skills in science and incorporate this into their current understanding of the world.

When designing a teaching sequence, it is important to consider the knowledge and skills that students will need in the final Act phase. Consider what the students already know and identify the steps that need to be taken to reach the level required. How could you facilitate students’ understanding at each step? What investigations could be designed to build the skills at each step?

Read more about using the LIA FrameworkThe Investigate routine provides students with an opportunity to explore the key ideas of science, to plan and conduct an investigation, and to gather and record data. The investigations are designed to systematically develop content knowledge and skills through increasingly complex processes of structured inquiry, guided inquiry and open inquiry approaches. Students are encouraged to process data to identify trends and patterns and link them to the real-world context of the teaching sequence.

When designing a teaching sequence, consider the diagnostic assessment (Launch phase) that identified the alternative conceptions that students held. Are there activities that challenge these ideas and provide openings for discussion? What content knowledge and skills do students need to be able to complete the final (Act phase) task? How could you systematically build these through the investigation routines? Are there opportunities to build students’ understanding and skills in the science inquiry processes through the successive investigations?

Read more about using the LIA FrameworkConsequentialism and deontology

Introduce the idea that decisions are not a matter of right or wrong. Instead, it is important to understand the reasons why an ethical decision was made.

(Slide 78) Explain that students will use two approaches (consequentialism and deontology) to examine the ethics of a decision that will be made by an autonomous car.

Explain that:

- Consequentialism looks at the final outcome of a decision and decides if it was good or bad (the end justifies the means).

- Deontology looks at the individual actions and decides if they are good or bad (what was the intention of the action?). The consequences do not matter.

✎ STUDENT NOTES: Write the definition of consequentialism and deontology.

(Slide 79) Other ways to consider ethics are to use ethical concepts to make decisions. Two of these are:

- Minimise harm (the least number of people harmed)

- Maximise the benefits (who will people/society most need or benefit from)

✎ STUDENT NOTES: Write the ethical concepts of minimise harm and maximise benefits.

(Slide 80) Provide students with a copy of the Ethical dilemma Resource sheet and the Ethical dilemmas Resource cards.

Explain that students should:

- examine each dilemma and identify what actions the car could take.

- decide if they will use the ethical concepts of either ‘minimise harm’ or ‘maximise benefits’ for their decision-making process.

- use consequentialist and deontological approaches to identify the action the car should take.

✎ STUDENT NOTES: Complete the Ethical dilemma Resource sheet.

Ethical outcomes

The ethical dilemma scenarios are divided into two types.

The ethical dilemma scenarios are divided into two types.

The first type of scenario (Tunnel, Age and Tree) has three options: to continue straight, to swerve left or to swerve right. The differences between left and right swerves make no reference to which side the oncoming traffic lane is on. Instead, these options are differentiated by who will be affected by the crash. For the Tunnel scenario, the people affected are the car’s own occupants or the occupants of the passing car (it is assumed that the bus passengers are sitting above the levels of the car and are not physically affected if the bus is rear-ended). For the Age scenario, the choice is between a young girl and an old lady. For the Tree scenario, it is a single pedestrian or a crowd of schoolchildren. All current autonomous cars are not able to make distinctions between a single pedestrian or a crowd of school children. For this reason, only two kinds of option merit consideration: the car either swerves, or continues straight, with each option involving danger to a different subset of participants in the scenario. Assume that the car will not be able to stop in time.

The second type of scenario (Swerve and Truck) has two options: swerve or continue straight on. It can be safely assumed that the swerve is in the direction away from the oncoming traffic lane. A car that veers into the oncoming traffic lane risks collisions at much higher relative speeds since its speed will be added to the speed of oncoming vehicles. For this reason, an autonomous car should never move into the lane of oncoming traffic.

The ethical dilemma scenarios are divided into two types.

The first type of scenario (Tunnel, Age and Tree) has three options: to continue straight, to swerve left or to swerve right. The differences between left and right swerves make no reference to which side the oncoming traffic lane is on. Instead, these options are differentiated by who will be affected by the crash. For the Tunnel scenario, the people affected are the car’s own occupants or the occupants of the passing car (it is assumed that the bus passengers are sitting above the levels of the car and are not physically affected if the bus is rear-ended). For the Age scenario, the choice is between a young girl and an old lady. For the Tree scenario, it is a single pedestrian or a crowd of schoolchildren. All current autonomous cars are not able to make distinctions between a single pedestrian or a crowd of school children. For this reason, only two kinds of option merit consideration: the car either swerves, or continues straight, with each option involving danger to a different subset of participants in the scenario. Assume that the car will not be able to stop in time.

The second type of scenario (Swerve and Truck) has two options: swerve or continue straight on. It can be safely assumed that the swerve is in the direction away from the oncoming traffic lane. A car that veers into the oncoming traffic lane risks collisions at much higher relative speeds since its speed will be added to the speed of oncoming vehicles. For this reason, an autonomous car should never move into the lane of oncoming traffic.

The Inquire phase allows students to cycle progressively and with increasing complexity through the key science ideas related to the core concepts. Each Inquire cycle is divided into three teaching and learning routines that allow students to systematically build their knowledge and skills in science and incorporate this into their current understanding of the world.

When designing a teaching sequence, it is important to consider the knowledge and skills that students will need in the final Act phase. Consider what the students already know and identify the steps that need to be taken to reach the level required. How could you facilitate students’ understanding at each step? What investigations could be designed to build the skills at each step?

Read more about using the LIA FrameworkFollowing an investigation, the Integrate routine provides time and space for data to be evaluated and insights to be synthesized. It reveals new insights, consolidates and refines representations, generalises context and broadens students’ perspectives. It allows student thinking to become visible and opens formative feedback opportunities. It may also lead to further questions being asked, allowing the Inquire phase to start again.

When designing a teaching sequence, consider the diagnostic assessment that was undertaken during the Launch phase. Consider if alternative conceptions could be used as a jumping off point to discussions. How could students represent their learning in a way that would support formative feedback opportunities? Could small summative assessment occur at different stages in the teaching sequence?

Read more about using the LIA FrameworkSharing the ethics

(Slide 81) Select one of the ethical dilemmas and discuss it as a class. Model a Socratic approach to the discussion, including:

- the teacher acts as a facilitator not a lecturer.

- ask open-ended questions to stimulate deep thought.

- challenge assumptions about how/why actions will minimise harm or maximise benefits.

- foster active listening so that follow-up questions are asked.

- draw as many students into the conversation as possible.

- allow students time to think before answering questions.

- encourage students to provide evidence or examples.

- summarise and reflect when appropriate.

- What is your initial decision to this situation?

- What action could the car have taken?

- Did you use a minimise-harm approach or a maximise-benefit approach? Was there any difference to these approaches when you were making decisions?

- Is anyone’s life more important than another person? Why or why not?

- Who might you (as the driver) sacrifice your life for? Why?

- Would your decision change if your family was in one of the groups? Why?

- Is the number of lives saved more important than whose life is saved? Why?

- What are the challenges of having to make these decisions years before the actual event?

Reflect on the lesson

You might invite students to:

- consider how their initial reaction to a dilemma might be different from a considered option. How would this reflect an instinctive decision vs programming an autonomous car?

- prepare an argument about who should be at fault when an autonomous car crashes.

An expert’s take on autonomous car ethics

The ethical and practical limits of swerving in self-driving cars.

“It takes some of the intellectual intrigue out of the problem, but the answer is almost always ‘slam on the brakes.’” - Andrew Chatham, principal engineer at Google’s X project developing self-driving cars , 2016

The decision for a self-driving car to swerve rather than perform an emergency stop has been presented in this lesson as a version of the trolley problem—choosing between hitting one person or multiple people. However, this framing oversimplifies the real-world physics and the practical limitations involved.

1. Controlled vs uncontrolled responses

Swerving is not just an alternative to braking. Swerving may cause the car to lose grip, skid, or hit unseen obstacles or people. Unlike the balanced options in a classic trolley problem, swerving is almost always a worse choice in terms of safety.

Swerving introduces new and often invisible hazards, such as:

- hidden pedestrians behind parked cars or foliage.

- kerbs, ditches, or uneven surfaces that may cause the car to roll.

- obstructed views leading to secondary accidents.

- confusing or startling other road users, causing chain reactions.

These factors make swerving inherently riskier, even when the road seems clear. Emergency braking is usually the safest and most controlled option.

2. Swerving vs braking in multi-vehicle scenarios

In complex cases involving other vehicles (e.g. a head-on collision with a large truck), braking might not prevent a crash but still reduces impact speed. Swerving could help only in rare, ideal circumstances (e.g. wide road, low kerb, no pedestrians). However, because most roads don’t meet these ideal conditions, and swerving risks are high, braking remains the safer default.

3. The problem with “high-information” scenarios

Some ethical scenarios assume the car can make value judgments. For example, choosing to hit a criminal over a law-abiding citizen or a drunk person over a sober one. But current technology cannot reliably assess personal traits like criminal records, intoxication, age, or vulnerability. To do so would require invasive access to personal data (e.g. biomonitors, government databases), raising serious privacy concerns and risks of data manipulation.

4. Uncertainty in real-time detection

Even making decisions based on the number of people at risk is unreliable. Sensors cannot accurately count individuals behind others or detect their physical vulnerability. People’s responses to danger (e.g. running, jumping) are unpredictable, especially if startled by a swerving car. The safest and most predictable course of action for all involved is not to swerve.

5. Rear-end collision risks

Emergency stops can lead to being rear-ended, but these crashes are generally:

- less severe than head-on or swerve-induced accidents.

- legally, the fault of the rear driver (not the self-driving car).

- already accounted for in car design (e.g. crumple zones).

Although injuries like whiplash can occur, these risks don’t outweigh the dangers of swerving into unpredictable environments.

Conclusion

Swerving might sound like a morally better option in theory, but in practice, it introduces far greater risk, uncertainty, and ethical complications. A self-driving car should almost always perform a controlled emergency stop, not swerve, unless highly specific, low-risk conditions are confirmed, which is rare in real life. Swerving endangers not only the passengers and the person in the car’s path but also bystanders, pedestrians, and other drivers. Therefore, designing autonomous vehicles to prioritise braking over swerving is the safest and most ethically consistent approach.

References

Davnall, R. (2020). Solving the single-vehicle self-driving car trolley problem using risk theory and vehicle dynamics. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(1), 431-449.

“It takes some of the intellectual intrigue out of the problem, but the answer is almost always ‘slam on the brakes.’” - Andrew Chatham, principal engineer at Google’s X project developing self-driving cars , 2016

The decision for a self-driving car to swerve rather than perform an emergency stop has been presented in this lesson as a version of the trolley problem—choosing between hitting one person or multiple people. However, this framing oversimplifies the real-world physics and the practical limitations involved.

1. Controlled vs uncontrolled responses

Swerving is not just an alternative to braking. Swerving may cause the car to lose grip, skid, or hit unseen obstacles or people. Unlike the balanced options in a classic trolley problem, swerving is almost always a worse choice in terms of safety.

Swerving introduces new and often invisible hazards, such as:

- hidden pedestrians behind parked cars or foliage.

- kerbs, ditches, or uneven surfaces that may cause the car to roll.

- obstructed views leading to secondary accidents.

- confusing or startling other road users, causing chain reactions.

These factors make swerving inherently riskier, even when the road seems clear. Emergency braking is usually the safest and most controlled option.

2. Swerving vs braking in multi-vehicle scenarios

In complex cases involving other vehicles (e.g. a head-on collision with a large truck), braking might not prevent a crash but still reduces impact speed. Swerving could help only in rare, ideal circumstances (e.g. wide road, low kerb, no pedestrians). However, because most roads don’t meet these ideal conditions, and swerving risks are high, braking remains the safer default.

3. The problem with “high-information” scenarios

Some ethical scenarios assume the car can make value judgments. For example, choosing to hit a criminal over a law-abiding citizen or a drunk person over a sober one. But current technology cannot reliably assess personal traits like criminal records, intoxication, age, or vulnerability. To do so would require invasive access to personal data (e.g. biomonitors, government databases), raising serious privacy concerns and risks of data manipulation.

4. Uncertainty in real-time detection

Even making decisions based on the number of people at risk is unreliable. Sensors cannot accurately count individuals behind others or detect their physical vulnerability. People’s responses to danger (e.g. running, jumping) are unpredictable, especially if startled by a swerving car. The safest and most predictable course of action for all involved is not to swerve.

5. Rear-end collision risks

Emergency stops can lead to being rear-ended, but these crashes are generally:

- less severe than head-on or swerve-induced accidents.

- legally, the fault of the rear driver (not the self-driving car).

- already accounted for in car design (e.g. crumple zones).

Although injuries like whiplash can occur, these risks don’t outweigh the dangers of swerving into unpredictable environments.

Conclusion

Swerving might sound like a morally better option in theory, but in practice, it introduces far greater risk, uncertainty, and ethical complications. A self-driving car should almost always perform a controlled emergency stop, not swerve, unless highly specific, low-risk conditions are confirmed, which is rare in real life. Swerving endangers not only the passengers and the person in the car’s path but also bystanders, pedestrians, and other drivers. Therefore, designing autonomous vehicles to prioritise braking over swerving is the safest and most ethically consistent approach.

References

Davnall, R. (2020). Solving the single-vehicle self-driving car trolley problem using risk theory and vehicle dynamics. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(1), 431-449.