What is force?

Force is a push or pull acting on an object as a result of its interaction with another object.

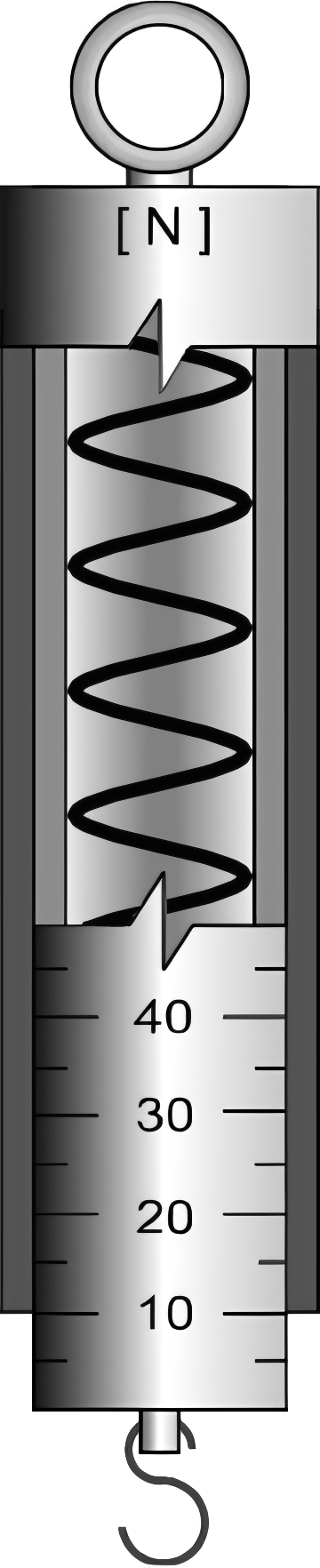

The measurement of force

Force is a quantity that is measured using a standard unit known as the Newton (abbreviated to ‘N’). One Newton is the amount of force to give a 1 kg mass an acceleration of 1 m/s every second. We write this as 1 Newton = 1kg.ms-2.

In the science classroom, forces are commonly measured using a Newton meter or force meter.

What can forces do?

Forces act on objects as a result of interactions. Forces change the motion of an object; they can make stationary objects move and cause moving objects to speed up, slow down, or come to a stop. Forces can change the direction an object is moving and can even change its shape. In Years 7 and 8, a good working definition of force is: A force is a push or a pull.

Forces have magnitude and direction

Intuitively, we know that a push or a pull has both magnitude and direction. We call something that has both magnitude and direction a vector quantity.

The magnitude of the force refers to the size or amount of force exerted, for example, a strong or weak kick (push force) on a soccer ball.

To fully describe a force, we must describe both its magnitude and direction. For example, a 5 N force acting on an object is not a complete description—a 5 N force to the right acting on an object is a more complete description. 5 N is the magnitude, and ‘to the right’ indicates the direction of the force.

Free-body diagrams

As forces have direction, it is common to represent the forces in an interaction using diagrams called free-body diagrams. In these diagrams, forces are represented by an arrow. The length of the arrow represents magnitude and the direction of the arrow shows the direction in which the force is acting. In Years 7-10, students can represent the relative strength of forces by the length of the arrow. Longer arrows in the direction of the force are used to represent a larger force, while a shorter arrow in the direction of the force is used to represent a smaller force.

In Years 11 and 12, senior physics students often draw free-body diagrams as a sketch to assist in analysing a scenario, often being asked to resolve vectors to determine the net force acting on the object. Senior students draw vector diagrams and use either the ‘head-to-tail’ method or trigonometric techniques to find the resultant vector (or net force).

Drawing free-body diagrams

For Years 7-10 students to understand how to draw free-body diagrams, they first need to understand the different types of forces (called external forces) that can act on an object in an interaction. A description of the different categories of forces is given below.

To draw a free-body diagram:

- Draw a simple representation of the object being considered. Often, a simple shape like a square box is drawn.

- Identify the different types of forces acting on the object—that is, the external forces.

- Determine the direction the different types of forces are acting on the object.

- Add arrows for each force to the simple shape in the appropriate direction and label according to its type.

Examples of free-body diagrams

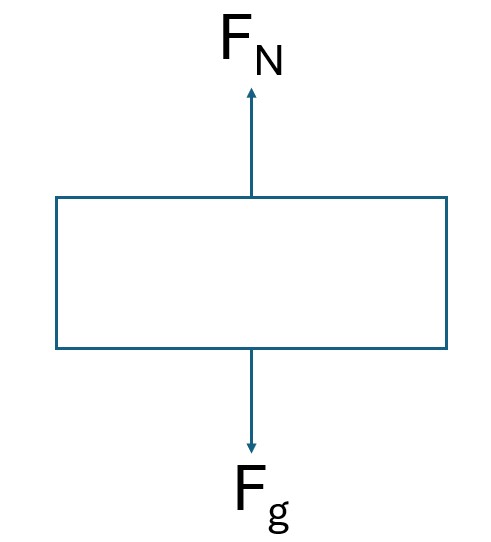

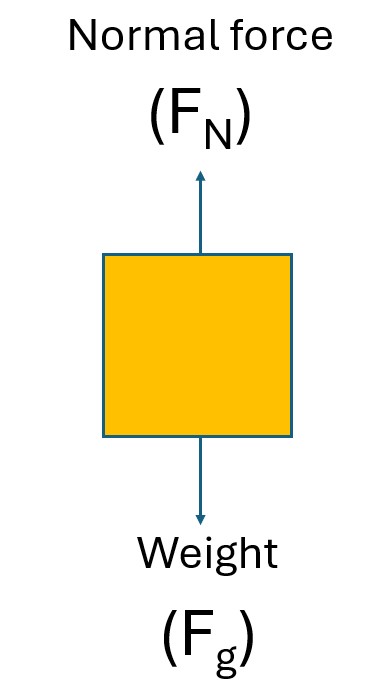

Scenario 1: A book is at rest on a tabletop.

A free-body diagram for this situation looks like this:

where $F_N$ is the normal force and $F_g$ is the gravitational force.

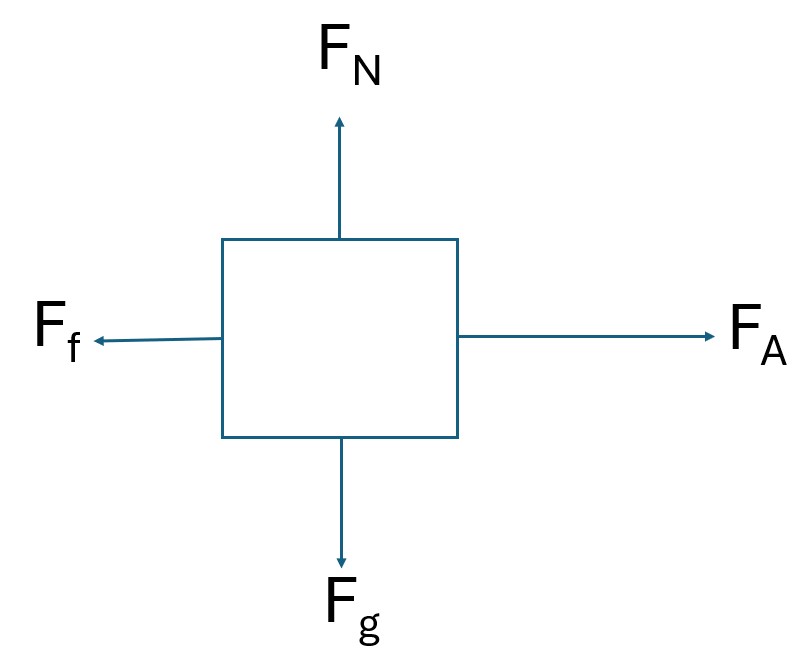

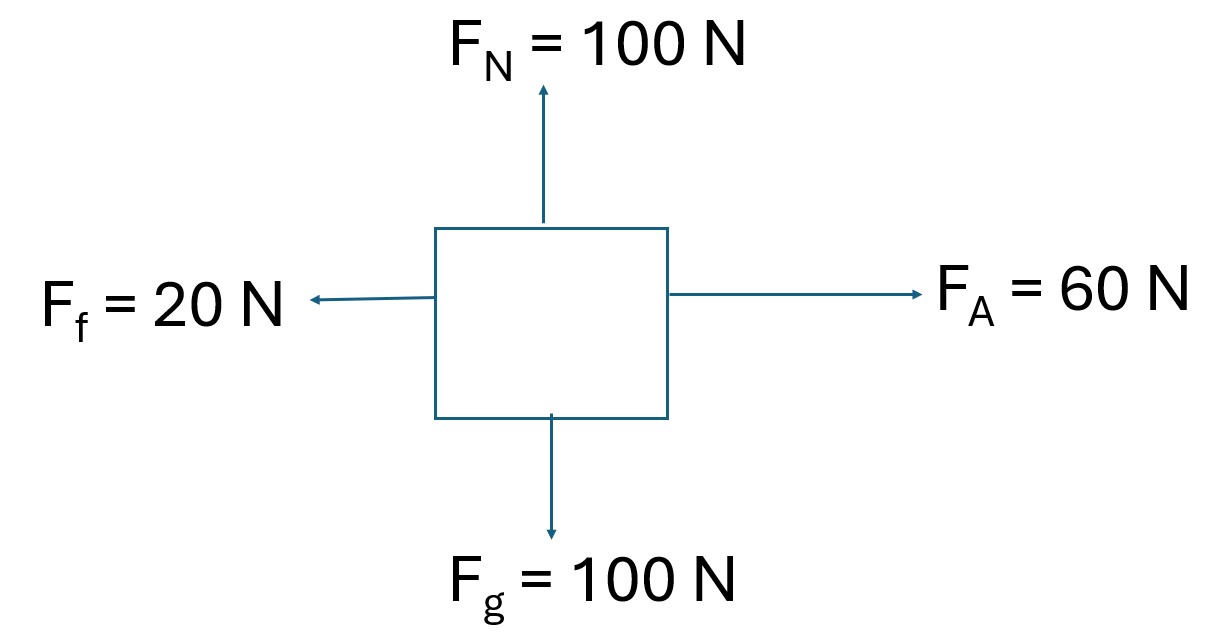

Scenario 2: A force to the right is applied to a book to move it across a desk so that it accelerates to the right. Frictional forces are considered, but air resistance will be neglected.

A free-body diagram for this situation looks like this:

Note that the size of the applied force arrow is larger than the frictional force. This provides a visual indication that there is a net force on the object that causes it to accelerate to the right.

Newton’s laws of motion

Newton’s first law of motion

Free-body diagrams are very useful in analysing forces acting on a system and are used when applying Newton’s laws of motion. Newton’s first law of motion, also known as the law of inertia, states that an object will remain at rest (or move in a straight line with constant speed) unless acted upon by a net external force. This law explains the behaviour of objects in terms of their motion (or lack thereof) and the role of forces in changing that motion.

Inertia

Inertia is the tendency of an object to remain at rest or to remain in motion with constant velocity. Inertia is the natural tendency of objects to resist changes in their motion. Inertia is the cause of a jolt when a car suddenly starts or stops—your body wants to stay in its current state (at rest or in motion) because of inertia.

Newton’s first law was built on ideas about motion developed by Galileo. His first law essentially says that a force is not needed to keep an object in motion. A predominant idea at the time was that force was needed to keep an object moving. Instead, Newton’s first law of motion states that a book pushed along a desk will eventually come to rest, not because of an absence of a force but due to the presence of a force.

Mass and inertia

Some objects have more inertia than others. The resistance to changes of motion varies with an object’s mass. Heavier objects are harder to start moving and harder to stop once they are moving. The greater the inertia of an object, the greater its mass. Mass is therefore a measure of an object’s inertia—its resistance to acceleration when a force is applied.

Newton’s second law of motion

Newton’s second law of motion describes the relationship between force and changes in motion.

Through experimentation, scientists have determined that acceleration is proportional to the net force applied on an object or system. When a small force is applied to a ball to make it move along a desk, it will not move with as large an acceleration as when a large force is applied.

It has also been found that acceleration is inversely proportional to the mass of the object or system. The larger the mass, the smaller the acceleration produced by a given force. The same net force applied to a car will result in a smaller acceleration than when applied to a scooter.

If these relationships are represented in an equation, then Newton’s second law of motion can be expressed as: $a=\frac{F_{net}}{m}$.

This is also commonly written as: $F_{net} = ma$.

Newton’s third law of motion

Newton’s third law of motion is commonly stated as: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. This law explains how forces always come in pairs. When one object applies a force on another object, the second object applies a force of equal magnitude but in the opposite direction on the first object.

This terminology incorrectly implies that one of the forces is the initiator of the interaction and that the other is a response. The correct idea is that every force represents an interaction (specifically, a push or a pull) between two objects. There is no such thing as a single force.

Types of forces

One way that forces can be categorised is based on whether the force resulted from the contact or non-contact of the objects interacting.

Contact forces

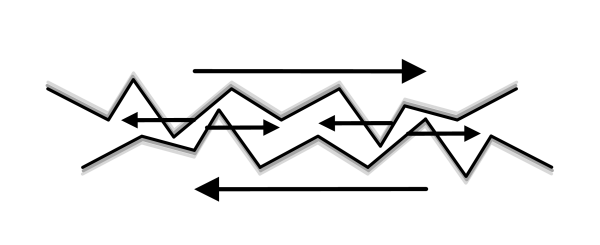

Frictional force

Friction results from two surfaces being pressed together closely and as such, depends on the surface and how close the contact is. At a microscopic level, surfaces that look smooth actually have tiny bumps and grooves. As the two surfaces slide past each other, these irregularities catch and resist motion, creating friction.

There are two types of friction—static and kinetic (sometimes called sliding friction).

- Static friction results when two surfaces are at rest relative to each other, and a force exists on one of the objects. For example, static friction exists between a large box and the ground on which it sits to prevent it from moving when pushed with 5 N of force.

- When the box is pushed with 10 N of force, it starts to slide from its resting position and is set into motion. Kinetic friction (the ground acting on the box) results when the object is in motion.

Students in Years 7-10 will commonly only be considering kinetic friction and drawing a horizontal arrow, labelled as $F_f$, in the opposite direction to the object’s motion in free-body diagrams. Senior students perform calculations of static and kinetic friction.

Applied force

Applied force is a force that is applied by a person or object on another object. For example, an applied force is the push force on the box. It is labelled as $F_A$ on a free-body diagram.

Applying Newton’s third law of motion—normal force and tension force

Normal force

Normal force is one acting from a surface onto an object resting on it. The size of the normal force will be equal in size to the force of the object pressing on it and it is always perpendicular to the surface in question. This force is labelled as $F_N$ on a free-body diagram. This force is a Newton’s third law reaction force to the object’s force on the surface. For an object at rest, like a box on a desk, the normal force is the force needed to support the weight of the box. This normal force would be equal to the weight of the object (as a consequence of Newton’s second law) but acting in the opposite direction.

Tension force

Tension force is a force along the length of a rope or cable. It is labelled as $F_T$ on a free-body diagram. Similarly, this force is a Newton’s third law reaction force.

Non-contact forces

Gravitational force

When air resistance is ignored, all objects near the Earth’s surface fall with an acceleration of approximately 9.81 ms-2. This value of acceleration is labelled ‘g’ and is referred to as acceleration due to gravity. Gravity is the force that causes non-supported objects to accelerate towards the centre of the Earth. The magnitude of this force is known as weight and is determined using the formula: $W=mg$ where m = the mass of an object (units kg).

Even though Newtonian gravity is not the exact description of the universe, for students in Years 7-10, the Newtonian view that gravitational force is universal and all objects attract each other with the force of gravitational attraction still gives an accurate description of the universe under the wide range of everyday circumstances discussed in classrooms.

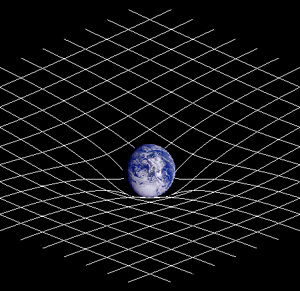

The modern understanding of gravity

Einstein’s theory of general relativity, developed in the early twentieth century, states that gravity is the curvature of spacetime caused by mass (or energy). Einstein’s theory can be summarised as: matter tells spacetime how to curve, spacetime tells matter how to move.

Gravity is warped or curved space (or more correctly, spacetime) caused by mass. A massive object warps the surrounding spacetime and other smaller objects follow these curves so that they appear to be ‘pulled’ towards the heavier object. Planets orbit the sun not due to a magical pull but because they are following the curved path (called a geodesic) in spacetime created by the Sun.

Large objects, like the Earth, distort spacetime but can also affect time. For example, time passes more slowly on Earth’s surface than for objects farther from the surface, such as a satellite in orbit. The very accurate clocks on global positioning satellites must correct for this. They slowly keep getting ahead of clocks at Earth’s surface. This is called time dilation, and it occurs because gravity, in essence, slows down time. In black holes, where gravity is hundreds of times that of Earth, time passes so slowly that it would appear to have stopped to a faraway observer of the black hole.

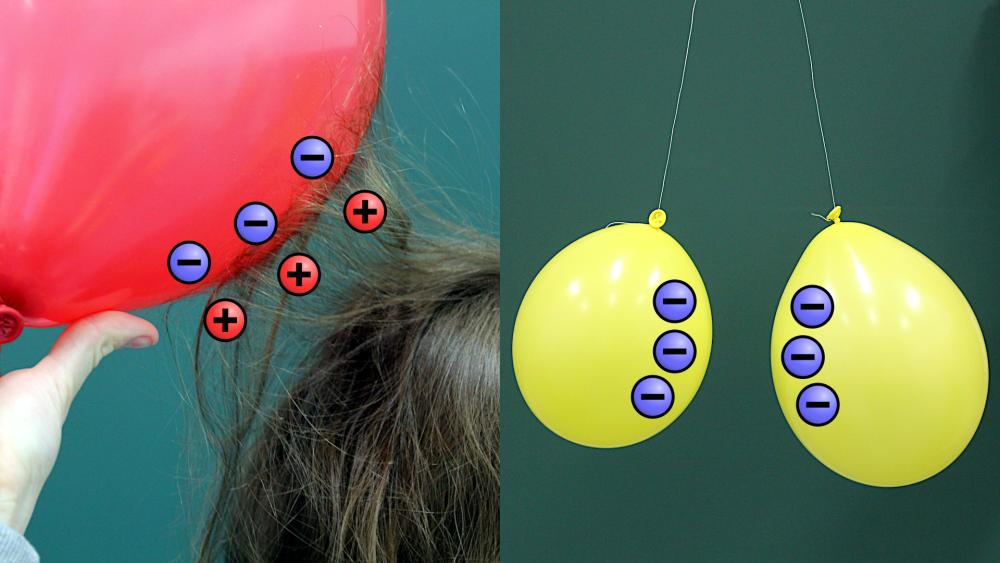

Electric force

Electric force is the attraction or repulsion interaction between any two charges or charged objects. An example of a charged object is a balloon which becomes negatively charged after it is rubbed on hair.

Charges (like electrons) or charged objects that have the same charge (both negative or both positive) will experience a repulsive force, and charges or charged objects with different charges (one positive and one negative) will experience an attractive force. This will change the object’s motion.

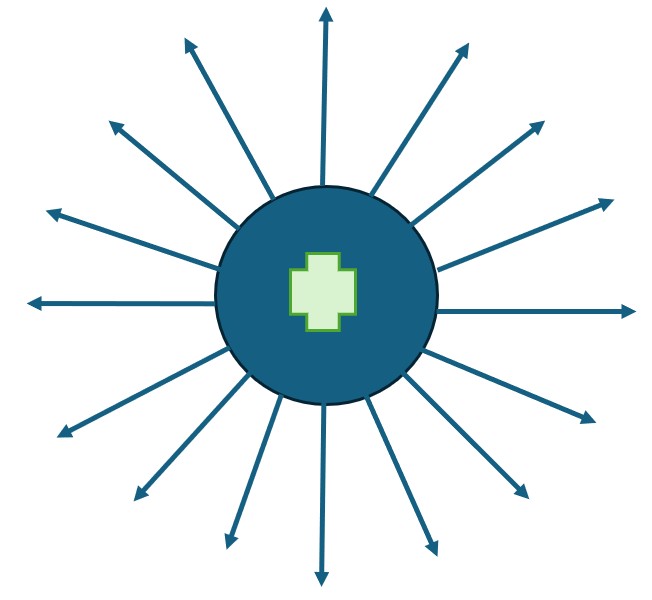

This type of force is considered a non-contact force as a charged object can affect the motion of another object at a distance. For example, holding a charged piece of PVC rod near (but not touching) a neutral aluminium can or a charged hanging balloon will attract or repel the object. This is because an electric field is established in the region surrounding a charge or charged object. A charged object will experience an electric force in this field.

The strength of the electric force depends on the magnitude of the charges (measured in Coulombs) and the distance between the charges. The electric force increases when the magnitude of the charges increases or the distance between the objects decreases. This relationship between charge, distance and force is expressed by Coulomb’s Law, which is used by senior students.

Magnetic force

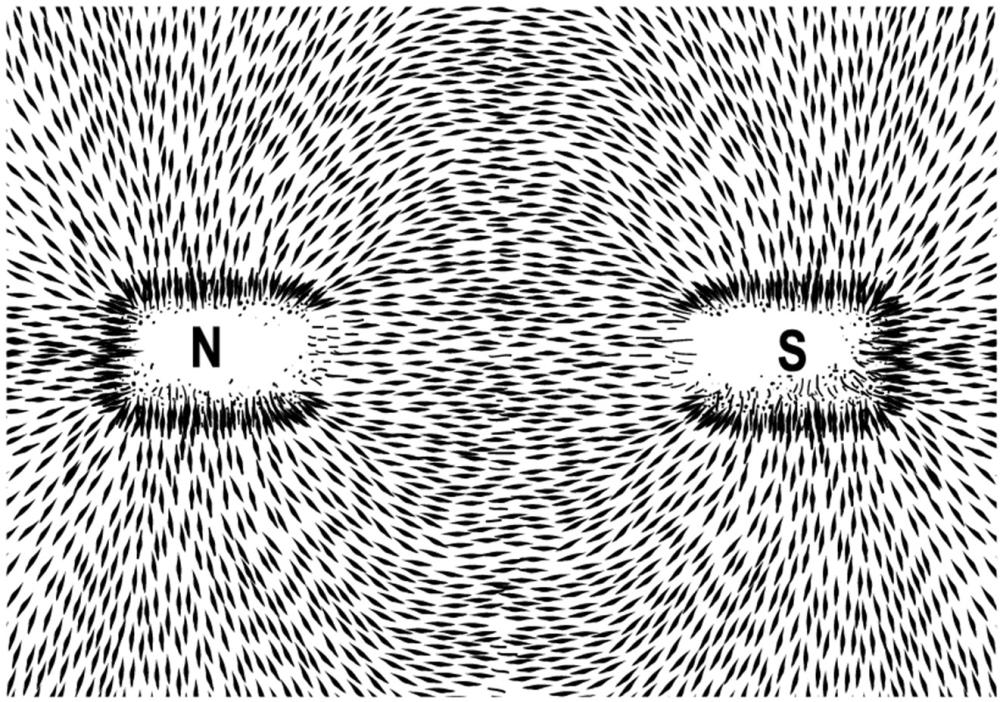

Permanent magnetic force

A magnet is a material that generates a magnetic field. Magnets only attract materials composed of iron, nickel, and cobalt. These materials are described as being ‘magnetic’. Steel is attracted to magnets as it is mostly made of iron. Most other materials, such as wood, plastic, aluminium, silver, and copper, are not attracted to magnets and are called ‘non-magnetic’.

A magnetic field is the region around a magnet in which the magnet exerts force. Many small pieces of iron, called iron filings, are used to show the magnetic field around a magnet. The iron filings experience magnetic force and align along the field lines to form a pattern of lines. The arrangement of the magnetic field lines depends on the shape of the magnet, but the lines always extend from one pole to the other pole. The force is weaker farther away from the magnet.

Temporary magnetic force

When an electrical current moves in a wire, a magnetic field is created around the wire, and an electromagnetic force is experienced by the charges in the wire. The magnetic field is not present when the current is switched off.

Apart from performing calculations to determine electric and magnetic force and field strengths, senior physics students learn that electricity and magnetism are two facets of the same phenomenon called electromagnetism.

Modern physics & forces

In senior physics, students learn that four basic forces account for all known phenomena and act through the exchange of carrier particles called bosons. The four forces are the gravitational force, the electromagnetic force, the weak force, and the strong force.

Unbalanced forces and motion

Newton’s first law of motion tells us that an object will stay at rest or in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced (or net) force. The unbalanced force is a result of a force not being completely balanced or cancelled by the other external forces acting on the object. In each of the examples below, an unbalanced (or net) force is acting on the object.

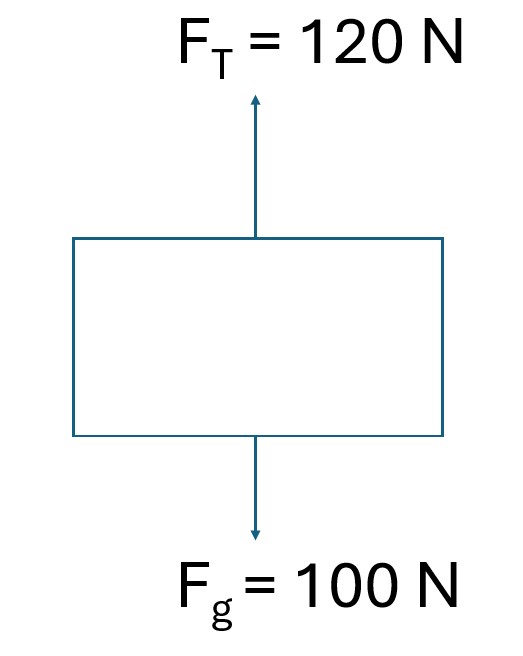

Example 1: An object is suspended on a rope in the air.

The object experiences a tension force upwards and a gravitational force downwards. The two forces have opposing directions but are not equal in magnitude and so are unbalanced. A net force will act on the object, and it will move upwards.

Example 2: An object is moving along a desk.

The object exerts a force of 100 N on the desk due to its weight, and the desk exerts an equal but opposite force on the object. These forces are balanced, and since there is no net force in the up and down direction, its motion will not change in those directions (it will stay on the desk). A push force is applied on the object, and the desk exerts a frictional force on the object. These forces act on the object in opposite directions, but they are of different magnitudes and hence are unbalanced. This means that the net force will act on the box in the horizontal direction, and it will move in the direction of the applied force (to the right).

Balanced forces

A common area of confusion for students when understanding force is understanding the difference between force pairs (as discussed previously in the section on Newton’s third law of motion) and balanced forces.

Force pairs–also called action-reaction forces—are interactions between two different objects. For example, a book exerts a force on the table, and the table exerts an equal but opposite force on the book. These two forces are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction, but do not cancel each other out as they act on different objects.

In contrast, balanced forces represent more than one force acting on the same object in such a way that they cancel each other out. In mathematical terms, the force vectors (or simply the forces) add up to zero. This means there is no net force acting on the object in the direction of the force vectors, and so there will be no acceleration in that direction. The motion of the object is not changed.

Simple machines

Simple machines usually achieve one or both of two things: they change the direction of a force and/or multiply the size of the force. The multiplication of force is called the mechanical advantage. Examples of simple machines include the lever, pulley, wheel & axle, inclined plane, and screw.

Linking force and energy

As previously discussed, forces are pushes or pulls acting on an object as a result of its interaction with another object. Energy, in contrast, is a fundamental property of an object and is defined as the ability or capacity of the object to do work. The energy of an object is a measure of its ability to cause change or motion, whilst force causes work to occur when the object is moved over a certain distance. Doing work causes energy to be transferred from one object to another (e.g. when a football player kicks a ball, kinetic energy from his foot is transferred to the ball) or transformed (e.g. when hands are rubbed together, friction transforms kinetic energy into heat energy).

References

Urone P P & Hinrichs R. (2023). Openstax College Physics 2e. <https://openstax.org/details/books/college-physics-2e>

Urone P P & Hinrichs R. (2023). Openstax High School Physics. <https://openstax.org/details/books/physics>

Henderson, T. (n.d.). Newton's laws. The Physics Classroom. <https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class>

Energy is a property of something that indicates its potential for change (ability to do work). Energy is always conserved, but it can be transferred or transformed.

Energy can appear abstract to students, but they can often detect it through the effect it has on their body: they can see patterns of light, and they can feel the warmth created by heat energy, though they cannot see or feel magnetic energy. Energy from the Sun drives the growth of plants and the development of rainstorms, while energy from chemical reactions gives life to animals and is also important to modern industry.

Some important characteristics of energy include:

- Energy exists in different forms, such as light, sound, heat, electricity and movement.

- Energy can be transformed (changed) from one form to another, for example, kicking a ball transforms chemical energy in our bodies to movement energy in the ball.

- Energy can be transferred from one location to another, for example, electrical energy moves along wires from a power station to our houses.

- Energy can be changed into other forms, but it cannot be created or destroyed.

- Energy can be stored in many ways. Batteries and fossil fuels are stores of chemical energy.

- Energy is the capacity to do work.

- Energy transfers involve change.

- Energy looks different in different situations—it can be transferred from one object to another.

- Electricity is a major way of transferring energy to our cities and homes.

- Heat/thermal energy is the energy that flows from hot to cold objects.

- Temperature is a measure of how hot or cold an object is, as measured by the thermometer.

- Energy transfer through different mediums can be explained using wave and particle models.

- Heat will flow from a hot object to a colder object until they are at the same temperature (equilibrium).

- Heat can be transferred through conduction, convection or radiation.

- It takes a lot of energy to heat or boil water and to melt ice.

Identifying energy as different energy forms may imply that energy is a material substance. This can lead to confusion for many students. The key aspect to consider is when something changes, energy is involved.

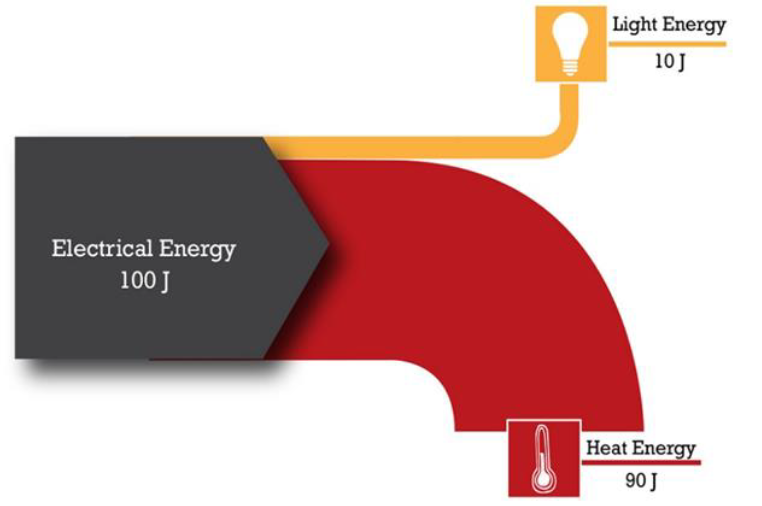

Sankey diagrams

Sankey diagrams summarise all the energy transfers underway in a process. The thickness of each line is proportional to the amount of energy involved. Sankey diagrams are named after Irish Captain Matthew Henry Phineas Riall Sankey, who used this type of diagram in 1898 in a publication on the energy efficiency of a steam engine.

This Sankey diagram for an electric lamp shows that most of the electrical energy is transferred as heat rather than light.

Kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy example

Most teachers start by throwing a ball in the air and describing the kinetic energy (KE) of the ball being transformed into gravitational potential energy (GPE). KE is initially provided to a ball while it is still in contact with the throwing hand. Once the ball leaves the hand there is no input of energy. As the ball rises the KE is transformed to GPE. This GPE is effectively stored in the height of the ball. (Strictly it is stored in the greater distance between the ball and the centre of the Earth.)

At the top of the flight, the ball stops momentarily (a difficult concept) at which point it has zero KE and maximum GPE. As the ball falls and loses height, the GPE is transformed into kinetic energy again.

Together kinetic and gravitational potential energies are referred to as mechanical energy.

Further information will be provided in the future.

| Alternative conception | Accepted conception |

|---|---|

| Heat is an entity or a measure of hotness. | Heat is the flow of energy from a warm object to a cooler one. |

| Heat only travels upwards. | Heat can travel upwards, but it can also travel in other directions through conductions and radiation. |

| Heat and temperature are the same. | Heat is the transfer of energy between two objects that are at different temperatures. Temperature is a measure of the kinetic energy of an object. |

| Heat is an entity or a measure of hotness. | Heat is the flow of energy from a warm object to a cooler one. |

| Energy is used up. | Energy may be transformed or transferred but it is always conserved. |

| Energy is a ‘thing’. | Materials and objects can have energy transferred to them. |

| Energy and force are interchangeable. | A force is an external effect that can cause an object to change its speed, shape, or direction. Leaning on a desk applies a push force on the desk. This force exists even if the desk does not move (it could cause change if the net force was unbalanced). Force is applied to an object, not transferred. Energy is a property of a system associated with the extent of movement of an object or the amount of heat within it. Energy changes from one form to another can be tracked. |

| Only living things have energy. | Energy can be transferred between objects. Batteries have chemical energy, cars have kinetic/motion energy. |

| Only objects in motion have energy. | Potential energy is the energy stored in a coiled spring, in a battery (chemical energy), or in an object that can fall. |

| Loudness and pitch are the same thing. | Pitch is how high or low a note is, while loudness is how loud or soft the note is. |

| Sound moves faster in the air than solids. | Sound needs particles to be transmitted. The closer together the particles (solid) the faster the sound will move. |

| You can see and hear an object far away at the same time. | Light travels faster than sound. |

| You can scream in space. | Sound requires a medium (with particles close enough to bump together) to be transmitted. This does not occur in space. |

| Heat is a kind of substance. | Heat is a form of energy that can be transferred or transformed. |

| Things expand when heated to make room for heat. | When objects are heated, the particles gain kinetic/movement energy. This faster movement means they take up more space and the object can expand. |

| Heat travels like fluid through objects. | Heat travels by conduction, convection, or radiation. |

| Objects in the same room can be at different temperatures (metals will be colder than wood). | Metals are good conductors of heat. Touching metal in a cold room will conduct the heat away from your body (making your hand and the metal feel cold). Wood does not conduct heat as well as metal. This keeps the heat in your hand (wood feels warmer than metal). |

| Things wrapped in an insulator will warm up. | An insulator maintains the heat in an object. A heat source is needed for an object to ‘warm up’. |

| The eyes produce light (cartoon-like) so we can see objects. | Light is a form of energy that comes from a source (not human eyes). |

| We see an object when light shines on it. | We see objects when the light bounces off an object and reaches our eyes. |

| White light is a colour. | The primary colours of light are green, blue, and red. When these are mixed, they produce white light. |

| A prism adds colour to light. | The different wavelengths of visible light bend in different amounts as they pass through a prism. This spreads the colours/wavelengths and produces a rainbow. |

| The grass is green because it produces green light. | The green leaves of grass reflect most of the green light (and absorb other colours). This is why we see the green colour. |

| The primary colours of light are the same as paint. | The primary colours of light are green, blue, and red. Mixing red and green light produces yellow light. |

| When light moves through a coloured filter, the filter adds the colour to the light. | A coloured filter selectively absorbs some colours and lets others through. For example, a red filter only lets red light through. |

| Light from a bulb only extends out a certain distance and then stops. | Light is spread over a greater area as it moves away from the source. This means there is less that reaches our eyes. |

| A mirror reverses everything. | Mirrors reverse images left to right (not up and down). |

| Light does not reflect from dull surfaces. | We see an object because it is a light source or the light has been reflected from its surface. |

| Light from a bright light travels further than light from a dim light. | The brightness of a light indicates the number of photons (packets of light) that are able to travel from the source to your eye. The light always travels the same distance but spreads out. More photons will reach your eye even when far away. |

| Static electricity and current electricity are two different things. | Both static and current involve electrically charged particles. In static electricity, the charged particles do not have a pathway to move. Current electricity has a pathway (usually wire). |

| Energy in an electric circuit is used by a light globe. | Electrical energy is transformed at the globe into light and heat energy. |

| Batteries store electrical energy. | Batteries store chemicals (chemical energy) that react to produce electricity in connecting wires. |

| You only need 1 wire to make a circuit. | Electricity must be able to flow from the negative terminal of a battery to the positive terminal. If only 1 wire is used, the bulb terminal must be in direct contact with the battery terminal. |

| The plastic in the wires keeps the electricity in (like water in a pipe). | Wires do not need plastic coating for the electrical current to flow. It does prevent potential short circuits. |

| Current is ‘used up’ in a circuit. | The current stays the same value in all locations of a series circuit. |

| The current moves from one end of the battery to the light. | When the battery is connected to a circuit, the current starts flowing in all parts of the circuit at the same time. |

References

AITSL. (n.d.). Resource. AITSL. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/tools-resources/resource/dispelling-scientific-misconceptions-illustration-of-practice

Allen, M. (2019). Misconceptions in Primary Science 3e. McGraw-hill education (UK).

Ideas for Teaching Science: Years 5-10. (2014, April 14). Resources for Teaching Science. https://blogs.deakin.edu.au/sci-enviro-ed/years-5-10/

Pine, K., Messer, D., & St. John, K. (2001). Children's misconceptions in primary science: A survey of teachers' views. Research in Science & Technological Education, 19(1), 79-96.

Redhead, K. (2018). Common Misconceptions. Primary Science Teaching Trust. https://pstt.org.uk/resources/common-misconceptions/

University of California. (2022, April 21). Correcting misconceptions - Understanding Science. Understanding Science - How Science REALLY Works... https://undsci.berkeley.edu/for-educators/prepare-and-plan/correcting-misconceptions/